Augmentation Matrix: Modifying Consonance Through Stretched Harmonics

A process of composing that relies exclusively on conventional compositional techniques without deeply examining the use of individual musical parameters is likely to result in creative choices limited by imitations and predictable solutions. While the use of already existing compositional strategies offers a familiar and comfortable expressive environment, it provides increasingly fewer opportunities for a development of unique compositional voices. In order to form new ideas, one may wish to first reflect upon the background of already existing compositional practices through other domains like physics, psychology, philosophy, technology, history, etc. Needless to say, while all ideas are potentially great, it is ultimately the practical execution that validates their relevancy.

One way to expand the musical vocabulary and subsequently its interpretations is by re-conceptualizing and restructuring the very building blocks of music making. Various musical traditions offer specific frameworks for the understanding/analysis of musical parameters such as pitch, harmony, rhythm, meter, tempo, timbre, structure, etc. A reflection upon Western musical evolution reveals, for example, a tendency to favor equal temperament, triadic harmonies, repetitious metric patterns and the use of orchestral instruments. Much like many other composers, I am interested to challenge these concepts, however I am even more fascinated to first examine our collective attraction to some of these Western musical preferences by trying to better understand how we perceive/conceive them. Specifically, I am most intrigued by our consonant/dissonant perception and its applications on our use of pitch.

A narrative of musical events, including their sonorities, provides us with sonic information ultimately triggering our subjective responses. While I believe that cultural conditioning and contextual considerations influence our cognitive response to consonance/dissonance, it is ultimately psychoacoustic factors that play a dominant role in determining its effects. It is true that one might, at least to some degree, expand one’s tolerance for a level of dissonance by listening or being culturally exposed to more dissonant sonorities. Likewise, the consonant effect of a sonority is stronger when preceded by a more dissonant sonority, in short, the larger the dissonant contrast between the two neighboring musical events, the more pronounced the effect of “roughness”. However, MRI test results show that newborns’ responses to consonance are similar to adults’ responses, thus diminishing the significance of cultural influence. Likewise, simply observing the weight of consonance throughout history, points toward our deep, innate, neurological response to the phenomena, leading us to hypothesize that our consonant/dissonant cognitive perception must be dependent much more on a psychoacoustics than any learned behavior. The latter hypothesis provides the inspiration for my musical system Augmentation Matrix.

Various psychoacoustic theories from Helmholtz to Sethares attempt to explain acoustic properties of consonance and many of them acknowledge a significant link between the harmonic series and sensory dissonance in Western music. While different theories examine the phenomena from different viewpoints, it seems clear that strong parallels and relationships between the two are statistically difficult to dismiss as coincidence. Upon extensive research of Western and Non-Western musical traditions, Sethares further argues that any sound spectrum, harmonic or non-harmonic, minimizes roughness when paired with a corresponding tuning (Sethares, 1999). Accordingly, the harmonic spectrum of Western pitched instruments not only correspond to equal temperament that is reasonably close to the natural tuning, but might be the catalyst for our tuning and at least some of the compositional structuring and musical “tendencies” to begin with. In short, our perception of consonant/dissonant order is to a great degree defined by implicitly perceived partials - a guiding web of spectral structures that serves as a reference and a context to musical syntaxes.

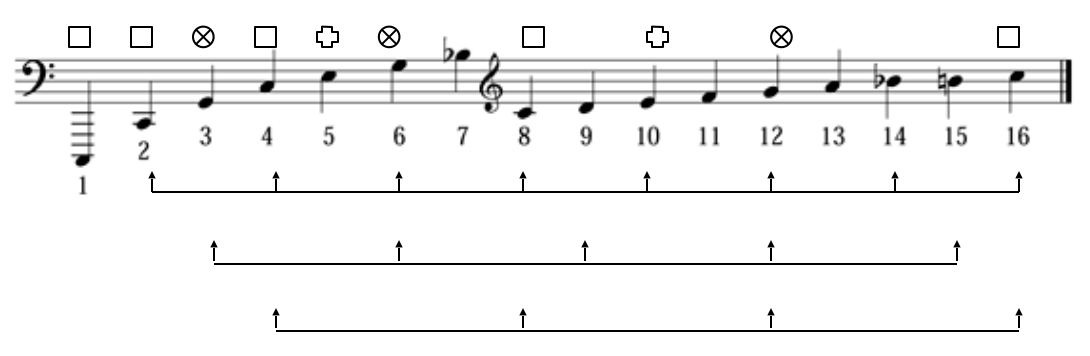

This innate relationship between sound spectra, tuning, our perception and consequently our music making can be understood further by analyzing the mathematical design of the overtone series. Its geometry and amplitude reveal yet another layer of information necessary to better understand the consonant/dissonant reality. The harmonic series consists of frequencies ascending through the integral multiples of the fundamental (if f indicates the frequency of the fundamental, then the frequencies of its overtones equal 2f, 3f, 4f, 5f, etc.). If any of these frequencies are substituted by n, therefore 2f = n, 3f = n, 4f = n, or 5f = n, etc., it follows that each order of n, 2n, 3n, 4n, 5n, etc. creates a transposition of a given series within the original series itself. It means that each harmonic of the harmonic series is a fundamental of a new harmonic series found in the given series through the multiples of n. It also follows that the order of the octaves in the harmonic series is determined by powers of two and if n again indicates the frequency value of the harmonic or its position in the series, then its octave repetitions equal n, 2n, 22n, 23n, 24n, 25n, etc.

Since the octave, the most consonant interval in Western music, is the lowest interval and therefore appears most frequently in this infinite series; and since the amplitude is highest at the lower end of the spectrum, we can further speculate connections between the order/structure of the overtone series and our perception of consonance. Furthermore, our entire musical system, including note names and the concept of “doublings”, is based on the cycles of octaves (note that there are traditions with other intervallic cycles, for example Georgian diatonic scales that are based on a system of fourths or fifths).

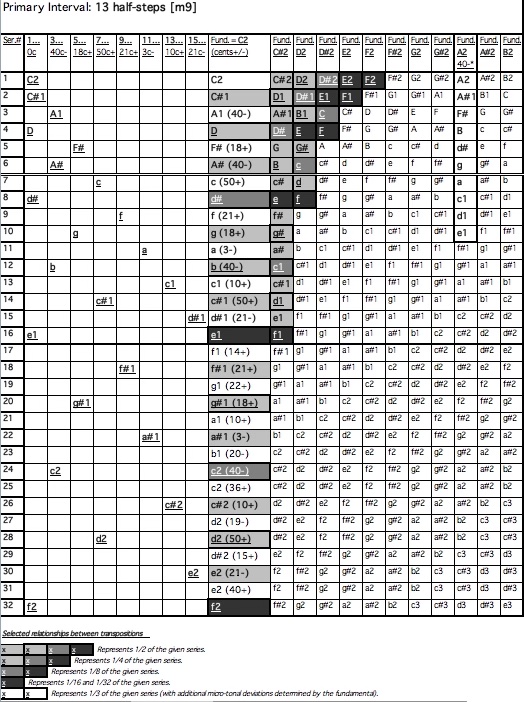

Except for the octave repetitions of the fundamental, the frequencies in the harmonic series are not the pitches of the tempered system used in Western tonal music. Using the formula: c = 3986 * log(f2/f1), where one half-step = 100c, I determined the precise microtonal deviations of the first thirty-two harmonics and calculated the following order of the overtone intervals expressed in cents: 1200c (octave = 12 x 100c), 702c, 498c, 386c, 316c, 267c, 231c, 204c, 182c, 165c, 151c, 138c, 129c, 119c, 112c, 105c, 99c, 93c, 89c, 85c, 80c, 77c, 74c, 71c, 67c, 66c, 63c, 60c, 59c, 57c, and 55c. This order is a structural foundation of my system.

The framework of my theory is based on a simple hypothesis: if there is indeed a connection between the structure of the harmonic series and our perception of consonance, is it possible to assume that this very same structure, only proportionally augmented (or diminished) would tilt the consonant effect in favor of a new hierarchical order where newly created “pseudo octaves” determined by the augmentations would replace the role of the octave? Likewise, if there is indeed a direct relationship between sound spectrum and tuning, can I expect maximum results when applying a new augmented series to additive sound synthesis as well as its corresponding tuning? With that in mind, one can build numerous augmentations where each partial, in this case an inharmonic one, becomes the beginning of the new transposed series, in this case an augmented one, while the first interval and all its exponential pairs become new primary intervals, new “functional octaves” of the augmentations. Due to practical compositional applications, I prefer working with augmentations based on tempered primary intervals, “pseudo octaves”. For example, when the intervals of the harmonic series (see the intervallic order expressed in cents mentioned above) are multiplied by a factor of 13/12 (see Fig. 2), the primary interval consists of exactly 13 half-steps (m9), when multiplied by 7/6, the primary interval becomes M9, when multiplied by 2, it is two octaves, etc.

While digital medium is best suited for working with Augmentation Matrix, acoustic applications are possible as well. The latter, due to the lack of their microtonal accuracy, matching sound spectrum, and precise tuning, reduce the consonant effect of the manipulation process, however they also reduce the microtonal deviations in relation to the tempered system since the augmentations provide theoretically an effect of “higher resolution” in relation to equal temperament. In addition to timbre and pitch, the numerical order can be applied to rhythm, tempo, and form. Creating various modes, harmonic progressions, circle of transpositions, “key” modulations with pivot notes/chords, etc., can be modeled after/translated from the Western tonal system by considering its presumed ties with the harmonic series; or can be treated independently by discovering unique characteristics, sounds, vocabulary and syntax of each augmentation. The latter process of exploring individual identities is my preferred choice of composing. It is, of course, possible to continue the series above the 32nd inharmonic partial and apply the process of the augmentation to the series of frequencies below the fundamental (stretched sub-spectra). It is equally possible to create diminished forms of harmonic series and apply similar compositional strategies to a process of diminution. Finally, it might be interesting to look for parallels between the proposed microtonal modes/models and various non-tempered tuning systems practiced around the world.

There is an infinite number of possible augmentations. If ignoring extreme registers and counting only the augmented series with tempered primary intervals, one can count 144 augmentations before all the notes of the series are the octave transpositions of the fundamental (the intervals are augmented 12 times). There are 156 augmentations before the order of a given series repeats (the intervals are augmented 13 times). Augmentation Matrix shows that there is a parallel between the sound structure and our perception of harmony; therefore, a deliberate change of the spectra matching the tuning and compositional structuring modifies the way we perceive intervals and chords. While any synergy of those components might increase sensory consonance, I choose to augment the harmonic series due to its recursive structure. In short, this system is a numerological game, an infinite matrix attempting to challenge our perception of consonance by creating a spectral algorithm based on stretched harmonics via calculated manipulations of timbre and pitch.